Literary Corner is going to new limits with this incredible piece of work from brother Tadhg. This perfectly addresses the theme of Literary Corner and provides very interesting insights as to how modern literature got started. It’s a bit longer than most articles, but I’m sure you will all agree that it’s worth the read. This also illustrates to some degree the amazing types of books Tadhg maintains in his library. Foe anyone who has not visited it, you should definitely make it a point to do so!

The First Printed Books – Mankind’s Third Revolution

by Tadhg Mac an Bhaird

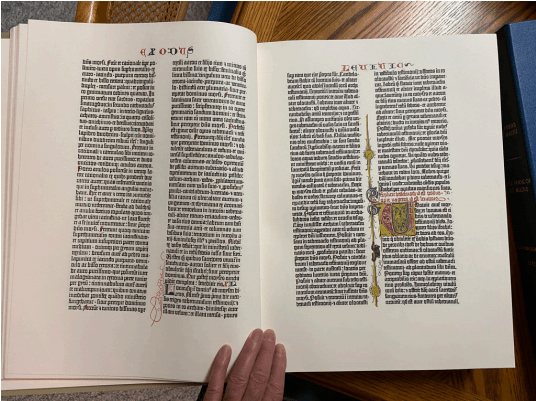

There are very few – if, indeed, any – milestones in human history that can equal the invention of the printing press. What ignited that technological spark, so profound that when it occurred over 500 years ago it changed the entire course of mankind? Two of those printed books, created during the fifteenth-century Renaissance, define the books we read today. The first book ever mass-produced using a printing press and moveable type was the Gutenberg Bible (the Biblia Sacra Latina), printed in Germany in 1455. The first “illustrated” book, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (or just Poliphilo), wherein illustrations were created specifically to compliment the text, was created in Italy about forty-five years later, in 1499, and is often considered the first of its kind. George Painter wrote in his Studies in Fifteenth-Century Printing: “The Gutenberg Bible is somberly and sternly German, Gothic, Christian and mediaeval; the Hypnerotomachia is radiantly and graciously Italian, classic, pagan and renascent. These are the two supreme masterpieces of the art of printing, and stand at the two poles of human endeavor and desire.” (See Figures 1 and 2).

The combination of methodology and technology Gutenberg used to create his Bible became conduits whereby all of civilization was revolutionized; the effect on mankind is incalculable. The Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, also rendered in English as The Strife of Love in a Dream, likewise incorporated innovations that are standard in all of our books today: an easy-to-read typeface, custom illustrations, artistic formatting to reduce eye-strain, and new-fangled punctuation marks such as the semi-colon. It is considered the most beautiful book of the Renaissance and was all the rage amongst Renaissance intellectuals; ironically, the text itself is impossible to read.

All of us reading this blog have one thing in common: we read books. We flip the pages, scroll our Kindles and iPads, crank up the volume on our audio books while we drive. There is little to mystify us in the mechanical effort of reading, but many were the mysteries needing to be solved that allows us to do so. Secrecy was paramount then; it wasn’t just the printing press that was the golden key to the printing of books, it was the mundane tools and equipment needed to make presses fulfill their function – each had to be invented. Accusations, theft, and cries of, “Foul!” were rife amongst the earliest book printers, perhaps none more so than between contemporaries of Johann Gutenberg. Of course, reams of lawyers were recruited by them all in attempts to get the upper hand.

Hitherto manuscripts were the source of written texts in Europe and the Middle East, preceded by the papyri of the Egyptians, a surprising number of which survived in the dry climate of the Egyptian desert. Manuscripts were tedious to produce and copy, and monasteries and universities employed myriad numbers of scribes to do the writing. The finished texts would be passed on from one academic to another, between churches, schools, governmental departments, and eventually wear out or fall to pieces. Contracting for new manuscripts was expensive, and scribes, in their haste to do the work, often made mistakes. Inevitably, errors were more pronounced when a scribe copied a text in a language he did not fully understand. By the High Middle Ages (c. 1000-1350 AD), Latin was the international language of church, government and academia but scribes often had insufficient fluency in Latin to ensure the nuances of an author’s text were being carried over into the copies

they were making. Long hours in cold, damp, or overheated scriptoriums often played upon the accuracy of their efforts and the quality of their materials, too. Slowly, those chronic irregularities were pondered and studied by parties interested in such matters – they were not printers or publishers, of course, because no such crafts existed. People interested in precision, however, began to look at ways to standardize texts without having to use outmoded techniques such as the endless carving of woodblocks, introduced by the Chinese in the twelfth century, and the inadequate moveable type introduced by a Korean emperor in the fourteenth century. Those

blockbooks, with carefully and laboriously hand-carved words and sentences, had limited practical applications – only a few texts could be done before new blocks were necessary.

Enter Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg. Born about 1400, a goldsmith by trade in the German city of Mainz, by the 1440s he was driven by the idea of producing a Latin Vulgate Bible that could be made in quantity for the use of clergy in every church. He jump-started the Modern Age in 1450 by doing just that, and the rapid changes that occurred following his legal battles – lawyers had their say – are the stuff of legend and intrigue. His covert research and his secretive development program, while overcoming some huge personal setbacks, changed world history. In 1444, for example, at the end of a five-year contract with three partners in Strasbourg, and still not having produced his printing press, the threat of war from an army of ragged French mercenaries had Gutenberg fleeing the city. He returned to Mainz and continued his work, finally printing his first book about 1450, a rudimentary, uninspiring little booklet of Latin grammar usually referred to as a Donatus, after the name of its fourth-century author; it was a mere token attempt, and no copies survive. The initial arrival of a printed book in Germany caused little fanfare. Striving mightily to keep his entire bible project secret until he was ready for business, Gutenberg in the 1450s had to expend ceaseless amounts of time and energy to overcome technological challenges. Lastly, to finance his momentous project, he had to raise capital and set up reserve funds to keep the business moving. Eventually, Johann Fust, Gutenberg’s financial backer, sued him for non-payment of debt, a debt Gutenberg struggled with for the rest of his life, and Fust eventually took control of Gutenberg’s printing presses and his bibles. The end result for Gutenberg was a small pension from the local archbishop, honoring his contribution to printing, but that was all.

Yet, he was a man of considerable stamina, and after printing Donatus he forged ahead with his plan to print the entire Vulgate bible (from the Latin “vulgata”, meaning “commonly used”). The most widely used bible of the Catholic Church, it was a late fourth-century translation by St. Jerome, a brilliant scholar who translated multiple Greek, Hebrew, Aramaic and Syriac manuscripts into a single Latin text. Despite Gutenberg’s ultimate success and the enormous cost of each printed bible, all of which were sold before the printing was completed, he never made a pfenning from his invention. Nevertheless, within fifty years, although the number of hand-copied manuscripts in libraries, monasteries and various collections in Europe numbered in the thousands, that number was dwarfed by an estimated 15-20 million printed books produced by the rapid expansion of printing on the Continent. That overwhelmed the production of manuscripts and within a few years the centuries-old craft of the scribes was made redundant. Science, literature, and the study of history exploded; Christian unity collapsed as controversial ideas were disseminated at lightning speed and questions began being raised by an impertinent public; explorers presented their amazing discoveries in never-imagined “new worlds”; kings began consolidating information about their territories, leading to the formation of nation-states, an altogether new concept for the Europeans. The wide and quick dissemination of information about trade and economic systems provoked sweeping changes in regional economies throughout Europe.

What, however, was his secret to making the printing press a reality, if not the press itself? As noted above, the Chinese and Koreans had earlier produced books using the same basic concepts Gutenberg did, but using carved wooden blocks for each page which were only useful for short works. The idea was virtually unknown in Europe. The Korean emperor Sejong, who lived at almost exactly the same time as Gutenberg, even simplified the Korean alphabet and created a moveable type, but resistance by the Korean aristocrats, who were unhappy about the conversion from Chinese characters to the new Korean Hangul, stifled any progress. There was no market for mass producing books in Asia – such an idea would take many decades to catch on in the Far East. Likewise in Europe – there was no urgency to mass produce books and little inclination to do so for the millions who had no idea how to read or write, anyway. Most of them would never see a manuscript in their lives except, perhaps, a glimpse during a church service. This was not so onerous as we may imagine: since only academics and clergy could read, a mass-market for manuscripts never existed.

However, the Chinese did revolutionize paper manufacturing – another critical step on the road to a usable printing press. In Europe, the real keys to Gutenberg’s creation of an efficient mechanical press were a new kind of linseed oil-based ink which wouldn’t smear on the newly devised paper, allowing a clear and precisely printed copy. But perhaps his most inspired invention was the type, i.e. the letters needed for printing. Gutenberg had at one time run a business stamping small, cheap metal mirrors for pilgrims visiting holy sites. That idea, and his training as a goldsmith, inspired him to create a type-casting hand mold for the letters of the alphabet. It also required a new metal alloy that would harden quickly, and the combination of tin, lead, and antimony he used had a relatively low melting point, cast clearly, and proved durable. Following an agonizingly long period of trial and error, he created 290 metal master characters of upper and lower case letters and punctuation which could be rapidly duplicated in the hand mold he’d invented. That was the real breakthrough. It was a simple, easy-to-use machine that is nonetheless frightfully difficult to describe or explain (the instructions are fourteen pages long), but he could quickly create as many letters as were needed and keep them readily available in his shop. There is almost no documentation explaining the workings for creating his hand mold, and the very few cryptic references to it in his correspondence only note “the four pieces”. This immediately replaced the cumbersome and labor-intensive method of hand-carving wooden blocks for each letter or page, useless for mass producing printed matter, and progress quickened. The original printing of the bibles took three to five years and each page used an average of 2,500-2,600 characters; with four to six presses being used at once, each with two

lock-ups of type on the sliding base, with likely another one or two each being produced at the same time, an estimated 50,000 characters of type needed to be on hand. That seems like a conservative number but is thought to be the amount that would have been in Gutenberg’s shop. Six pages of over 15,000 characters could be printed at one time. The development of the technical details remains obscure, and scholars have been involved in endless debates for centuries about what, precisely, Gutenberg invented – the debates continue full-steam ahead into the twenty-first century. Most Gutenberg bibles contained 1,286 pages bound in two volumes, yet almost no two are exactly alike. Of the 180 copies, some 135 were printed on paper, while the rest were made using vellum, a parchment made from calfskin. Due to the volumes’ considerable heft, it has been estimated that some 170 calfskins were needed to produce just one Gutenberg Bible from vellum. His method for printing books would remain essentially unchanged for the next 400 years. Less than thirty copies of that original run remain intact, and the last sale of a complete volume was in 1978, for $2.2 million. It is estimated that a complete text coming on the market today would fetch somewhere in the neighborhood of $35 million.

These large, heavy bibles, often hand-decorated by artists (“rubricators”) for wealthy patrons, quickly captured the imagination of scholastic Europe, and the race was on for books. Book production today remains comfortably in the millions. In the year 1999, Time Magazine recognized Gutenberg as the “Man of the Millennium”. John Man, in ‘Gutenberg: How One Man Remade the World with Words’, calls Gutenberg’s invention the ‘Third Revolution’ in the course of mankind’s four turning points during the past 5,000 years. The First Revolution was the invention of writing itself; the Second Revolution, the invention of the alphabet; the printing press was the Third, and the Fourth Revolution was the creation of the Internet.

Despite attempts by the craftsmen to keep the invention under wraps, printing presses swiftly became established in Europe, especially Germany and Northern Italy, as those who learned the book printing trade from the early masters began setting up their own shops. Those new shops often provoked contentious backlashes from other printers, and it was not uncommon for a printer to pack up and get out of town to save his presses from legal authorities and his skin from indignant mobs. The books devised by those print shops between 1455 and January 1501 are collectively referred to as incunables (incunabula is the plural Latin form), meaning “cradle” or “swaddling clothes”, i.e. the earliest stages or first traces in the development of books – the Gutenberg Bible is the first of those books. Most incunables are rare, but considering their sheer quantity, they can still readily be found for sale by rare booksellers on many websites. Printing throughout this period continued to expand into France, Spain, the Netherlands, and Britain. By 1500, about 40,000 titles had been printed in millions of copies – compared to the output in manuscripts, this was a mind-boggling achievement, and it was only the beginning.

The writing of books, also, progressed at an astonishing rate. During the incunable period, atlases and geographies, mathematical, scientific and theological books were followed by the latest discoveries in medicine, husbandry, and engineering, which in turn were followed by Classical learning, all at a lively pace. A village plagued by flooding could learn how to drain the surrounding bogs; recurring medical afflictions could now be explained to remote doctors and known cures described. Obscure and nearly lost works by ancient philosophers excited public debates. The books were not, as yet, practical to use. They were cumbersome and they were unbound; printers created hundreds of copies but binding was up to the book buyer to arrange. Printers were also quick to catch on to the financial burden of printing texts that were poor sellers: the enormous investments required in paper, ink and multiple mechanical devices, along with the training and wages of craftsmen, required a decent return on their investments if they were to stay in business. To make the most of their sales, they also required prompt and reliable transport: a printer in Italy spending weeks to prepare the works of Tacitus or Petrarch, for example, would be dismayed to hear of a Dutch or French printer doing the same and would put his own presses into high gear trying to beat his competitors to the new book fairs appearing in major cities, an undertaking that bordered on cutthroat. Europe’s first book fair was held in Frankfurt in 1478, and as the general public began to read, they clamored for more. Transport was an essential component.

A vexing problem for the printers was book size, exacerbated by the practice of many authors who included annotations alongside their texts. Books were usually printed in two columns per page, and their annotations or notes, expounding upon specific points within the main text (footnotes weren’t invented yet), consumed considerable space. That required larger pages to squeeze everything in. The problem was eventually tackled head-on by an Italian scholar with a passion for the classical authors of Greece and Rome, a teacher named Aldo Manuzio, better known by the Latin form of his name, Aldus Manutius. He became, arguably, the world’s first publisher, beginning his legendary Aldine Press in Venice in the 1490s. Printing, although still in its infancy in historical terms, was now spread throughout Europe, and printers like Aldus would implement key changes into how books were formatted, printed, marketed, and presented to the public.

Aldus Manutius was driven to bring the nearly forgotten ancient Greek texts and language to the eager scholars of Western Europe. Already, one of the most significant beneficiaries of printing was the humanities: works about poetry, grammar, history, moral philosophy and rhetoric, the very things that many of our modern authors utilize in novels to tell a story, were being printed by the thousands. Ancient Roman and Greek texts from Ovid, Virgil, Cicero, and from Aristotle, Plato, Herodotus and Polybius, could now be preserved and printed en masse for scholars throughout Europe and the Middle East. Aldus led the way and he was enormously successful at innovation. For example, he created punctuation marks such as the semi-colon that we still use. He banned the lengthy notes and annotations that swelled the size of books, and working with other craftsmen such as Francesco de Bologna, he created an italicized roman type that was much easier to read than the heavy Gothic texts produced in Germany. The clarity of the type allowed fonts that were much smaller, so much so that Aldus began creating books that a man could carry in his pocket – an extraordinary concept that allowed people to carry and read their books in public houses, in parks and parlors, and even, to the astonishment of many, in bed! His books were eagerly sought out, and famous authors such as Erasmus of Rotterdam would move into Aldus’ house to supervise the printing of their own books. During the course of his publishing ventures, at the very end of the fifteenth century, he printed, almost as a sideline, what is now considered the most beautiful book of the Renaissance and the most famous book in the world: the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili.

While easily recognized as a work of extraordinary refinement, the book itself is an enigma. To start with, no one really knows how to pronounce the title. The University of Texas Ransom Center, holding three copies, suggests the pronunciation “hip nair otto MOCK ee a PAHL if eel ee.” Adding to that bit of excitement, William H. Irvins, Jr., the curator of prints at New York’s Metropolitan Museum, writing in 1923 (Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 18, no. 11, Nov. 1923), called it “so dull that only the most pugnacious of readers can force his way through it.” (Considering the number of Renaissance-inspired bibliophiles who have actually read it, one could make a solid case that pugnaciousness is a nearly extinct attribute.) It is still disputed who the author was – Aldus, who printed the book on commission (it was backed by independent financing), published it anonymously and perhaps was uninterested in the true author since he was paid up-front. Scholars have variously attributed it to the famed Renaissance architect Leon Battista Alberti, to Lorenzo de Medici, and even to Aldus Manutius himself. It may have been the governor of one of the Roman provinces or a Dominican monk, both with the same name: Francesco Colonna. Most of the evidence, however, points to the latter, a randy, hard-living monk who was disciplined more than once for his loose living and whose abbot finally gave him the bill for reimbursing the cost of the printing. The Italian language was not yet standardized when Colonna penned his mind-twisting love story, and the text, a bizarre hybrid mix of the Tuscan Italian vernacular, Latin, and other languages, is virtually unintelligible. When the author couldn’t find quite the right word, he’d make one up. Jason Kottke, in his article Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (Kottke.org, June 12, 2008), cuts to the quick: “The Hypnerotomachia Poliphili is one of the most unreadable books ever published. The first inkling of difficulty occurs at the moment one picks up the book and tries to utter its tongue-twisting, practically unpronounceable title. The difficulty only heightens as one flips through the pages and tries to decipher the strange, baffling, inscrutable prose, replete with recondite references, teeming with tortuous terminology, choked with pulsating, prolix, plethoric passages. Now in Tuscan, now in Latin, now in Greek – elsewhere in Hebrew, Arabic, Chaldean and hieroglyphs – the author has created a pandemonium of unruly sentences that demand the unrelenting skills of a prodigiously endowed polyglot in order to be understood.” The description by the eminent twentieth-century bibliographer E.P. Goldschmidt in The Printed Book of the Renaissance (1947) is no less amusing: “Aldus Manutius … brought out Francesco Colonna’s Hymerotomachia Poliphili, which is in its essence a repertory of classical archaeology … it painfully incorporates the sketch-book of an archaeologist and the fruits of reading of a classical scholar within the framework of a laborious romance … The Poliphilo is a famous book because of its illustrations, but like some other great books it is written by a lunatic. Colonna was a cleric, locked away in a quiet provincial town, Treviso, who became so intoxicated with the new words, the new forms, the classic phrase and the classic ornament, that he burst into a voluminous and confused rhapsody into which he crammed all of his New Learning and he illustrated it with all the antique shapes and figures recently revealed to him and to the world. The Poliphilo is written neither in Latin nor in the vernacular, but in a strange hybrid new language of Colonna’s own devising, neither quite Latin nor quite Italian, and the book is as unintelligible as Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake.”

It is, however, the artistic and printing aspects of the book that we modern readers benefit from the most, but we are still not off the hook for answers. The 172 stunning woodcuts used to illustrated Poliphilo remain another source of mystery: while the actual author of the book is still disputed, even less is known about the artist who did the woodcuts – no one has a clue. Their design is generally attributed to Benedetto Bordon(e) of Padua, who was active in Venice from 1488 until his death in 1530. The spare and elegant illustrations reveal a careful study of ancient art as well as an interest in the new science of one-point linear perspective. The beauty of these anonymous woodcuts has led scholars through the years to associate their design with such famous artists as Andrea Mantegna, Gentile Bellini, or the young Raphael. They are only speculative. The unfortunate result of all those amazing woodcuts was that copies of the book were routinely cut up for the illustrations and the text discarded – sacrilege! Anthony Blunt, the British art historian-turned-Soviet spy, remarked in the 1940s that Polifilo “is one of those books which have suffered from being too well printed and too beautifully illustrated.” It does retain its hold as the finest book of the Renaissance.

These two enormously influential texts, the first and the last of the incunabula, and the methods used for their creation leave their mark on every printed book we read today. Their conception was nurtured through dogged determination, their physical creation was touched by genius and unrelenting tenacity, and their significance and influence on modern books and books trades today remains undiminished.

Figure 1 – The Gutenberg Bible, c. 1455 (facsimile copy)

Figure 2 – The Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, or The Strife of Love in a Dream, 1499

Bibliography

A variety of works from my own library were utilized for this article. The list may be useful for anyone

wishing to pursue their own further studies:

- Aldus and His Dream Book: An Illustrated Essay; Helen Barolini; New York: Italica Press, 1992;

- Aldus Manutius: Printer and Publisher of Renaissance Venice; Martin Davies; Malibu, California: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1995; originally published London, The British Library, 1995;

- Authentic Witnesses: Approaches to Medieval Texts and Manuscripts; Mary A. Rouse and Richard H. Rouse; Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 1991;

- The Beginning of the World of Books, 1450-1470. A Chronological Survey of the Texts Chosen for Printing During the First Twenty Years of the Printing Art. With a Synopsis of the Gutenberg Documents; Margaret Bingham Stillwell; New York: The Bibliographical Society of America, 1972;

- The Book in the Renaissance; Andrew Pettigrew; New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2010;

- The Bookseller of Florence: The Story of the Manuscripts that Illuminated the Renaissance; Ross King; New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2021;

- Bound in Venice: The Serene Republic and the Dawn of the Book; Alessandro Marzo Magno, trans. Gregory Conti; New York: Europa Editions, 2013;

- The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing 1450-1800 (Foundations of History Library); Lucien Paul Victor Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin, eds., Geoffrey Nowell-Smith and David Wootton, trans. David Gerard; London: NLB, 1976; originally published in French as ‘L’Apparition du Livre’, Paris, Editions Albin Michel, 1958;

- Editio Princeps: A History of the Gutenberg Bible; Eric Marshall White; Turnhout, Belgium: Harvey Miller Publishers, an imprint of Brepols Publishers, 2017;

- Gothic & Renaissance Bookbindings. Exemplified and Illustrated from the Author’s Collection. Volume I: Text; Volume II: Plates and Photographs (2 vols. complete); Ernst Philip Goldschmidt; Nieuwkoop, Amsterdam, The Netherlands: B. de Graaf–N. Israel, 1967; originally published London, Ernest Benn, and Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1928;

- Gutenberg: How One Man Remade the World with Words; John Man; New York: MJF Books, 2002;

- The Gutenberg Bible (Biblia Sacra Latina): Facsimile of the Gutenberg Printing; Johannes Gutenberg, printer; Norwalk, Connecticut: Easton Press, 2019;

- The Gutenberg Bible: Landmark in Learning; James Thorpe; San Marino, California: Henry B. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, 1999;

- Johann Gutenberg: The Man and His Invention; Albert Kapr, trans. Douglas Martin; Aldershot, Hampshire, England: Scolar Press, 1996; First English-language edition (third edition, revised by the author for first publication in English translation); originally published in German as ‘Johannes Gutenberg, Persönlichkeit und Leistung’, Munich, C.H. Beck, 1987;

- Johann Gutenberg and His Bible. A Historical Study; Janet Ing [now Freeman]; New York: The Typophiles, 1988;

- The Printed Book of the Renaissance. Three Lectures on Type, Illustration, Ornament; Ernst Philip Goldschmidt; Cambridge: Cambridge at the University Press, 1950;

- The Printed Word: Its Impact and Diffusion (Primarily in the 15th-16th Centuries); Rudolf Hirsch; London: Variorum Reprints, 1978;

- Printing and Publishing at the Aldine Press 1495-1585: An Introductory Handbook to the Life and Work of Three Generations of the Manutius and Torresani Families; Adam Mills; Cambridge, England: Adam Mills Rare Books, 2020;

- Printing, Selling and Reading, 1450-1550: Second Printing with a Supplemental Annotated Bibliographical Introduction; Rudolf Hirsch; Wiesbaden, Germany: Otto Harrassowitz, 1974;

- Printing and the Renaissance: A Paper Read before The Fortnightly Club of Rochester, New York; John Rothwell Slater; Forest Hills, New York: Battery Park Book Company, 1978;

- Studies in Fifteenth-Century Printing; George D. Painter; London: Pindar Press, 1984;

- The World of Aldus Manutius: Business and Scholarship in Renaissance Venice; Martin Lowry; Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1979

So,Tim, you must have shown me your personal copy of The Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, but I do not remember seeing this precious volume, which means I will have to revisit your amazing library for a viewing. A great article. Kevin, thanks for loosening your rules to share this with us.

LikeLike

My door is always open to my cousins!

LikeLike

Very interesting read! I tried to comment but they’re asking for a password. Too many passwords and my password “key” is in another room. haha

Sent from Mail for Windows 10

LikeLike

Not sure why they asked for a password. Your comment did come through.

LikeLike

Glad you liked it, Wanda! The library beckons!

LikeLike

I really enjoyed this article too. I learned a lot and would love to see your amazing library in person someday. Thank you for sharing

LikeLike

Thank you, Marian! My humble pile of books are ready!

LikeLike